|

There is a rumor floating around the Internet that the United States Constitution, which took effect on March 4, 1789, is a "secular document." What is meant by this claim is that the Constitution actually contains the doctrine of "the separation of church and state." And what is meant by that doctrine is that the government not only does not have a duty to worship and obey the God of the Bible, but that the Constitution imposes a duty on government not to acknowledge God at all, and to behave as though atheists are correct, and theists are wrong about God requiring anything of man.

According to this rumor, the U.S. Constitution prohibits all governments from acknowledging that God exists and that He has communicated His will to us, and we (and the governments we create) are ethically and morally obligated to obey His Commandments.

This rumor is a lie. Many people who repeat this lie may be well-intentioned, sincere people. But they are unwittingly propagating a lie.

The only way a person could sincerely believe that the U.S. Constitution was intended to give the federal government power to secularize America is if that person is a victim of educational malpractice, and labors under oblivious ignorance of law and history. In 1892, the United States Supreme Court, facing the initial wave of secularist ideas, forcefully declared that the United States is officially, legally, and constitutionally a Christian nation, thoroughly refuting the idea that the Constitution is a secularizing charter.

All 13 colonies were Christian Theocracies at least until 1776. The Declaration of Independence is a Theocratic document, in that it acknowledges that God is Supreme over Civil Government. ("Theocracy" = "God" + "rules") So from 1776-1789, at least, America was still a Christian Theocracy.

This page explains why the Constitution did not change the Theocratic character of America in 1789.

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention were reminded of the fact that the creation of America exhibits the hand of God. Read Benjamin Franklin's remarks on the subject of Divine Providence in the Constitutional Convention. James Madison, "Father of the Constitution," later reflected on how God heard the prayers recommended by Franklin, and helped create the Constitution.

Would it be wonderful if, under the pressure of all these difficulties, the [Constitutional] convention should have been forced into some deviations from that artificial structure and regular symmetry which an abstract view of the subject might lead an ingenious theorist to bestow on a Constitution planned in his closet or in his imagination? The real wonder is that so many difficulties should have been surmounted, and surmounted with a unanimity almost as unprecedented as it must have been unexpected. It is impossible for any man of candor to reflect on this circumstance without partaking of the astonishment. It is impossible for the man of pious reflection not to perceive in it a finger of that Almighty hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution.

Federalist #37

|

After the Constitution was ratified, Congress contemplated whether it should request the President to declare a national day of Thanksgiving to God. Atheists might tell us that the very suggestion was immediately shot down on the grounds that "the Constitution is a secular document!" The Annals of Congress for Sept 25, 1789 record these discussions:

Mr [Elias] Boudinot said he could not think of letting the session pass over without offering an opportunity to all the citizens of the United States of joining with one voice in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings He had poured down upon them. With this view, therefore, he would move the following resolution:

Resolved, That a joint committee of both Houses be directed to wait upon the President of the United States to request that he would recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.

Mr. [Roger] Sherman justified the practice of thanksgiving, on any signal event, not only as a laudable one in itself but as warranted by a number of precedents in Holy Writ: for instance, the solemn thanksgivings and rejoicings which took place in the time of Solomon after the building of the temple was a case in point. This example he thought worthy of Christian imitation on the present occasion; and he would agree with the gentleman who moved the resolution. Mr Boudinot quoted further precedents from the practice of the late Congress, [he was a member of the Continental Congress from 1778-79 and 1781-84 and President of the Continental Congress 1782-83] and hoped the motion would meet a ready acquiescence. [Boudinot was also founder and first president of the American Bible Society.] The question was now put on the resolution and it was carried in the affirmative.

On this very same day, Congress approved the final wording of the First Amendment.

The Congressional resolution was delivered to President Washington who heartily concurred with its request. On Oct 3, 1789, he issued the following proclamation:

|

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor, and Whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me "to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanks-giving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness."

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th. day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be. That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks, for his kind care and protection of the People of this country previous to their becoming a Nation, for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his providence, which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war, for the great degree of tranquillity, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed, for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted, for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed, and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

And also that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions, to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually, to render our national government a blessing to all the People, by constantly being a government of wise, just and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed, to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shown kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord. To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the increase of science among them and Us, and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.

Not a single person who signed the Constitution -- not one -- intended to create a "secular" document, meaning a document which gave the federal government the power to secularize our legal system and government. All the infidels on the Internet who claim that the Constitution is secular are wrong.

|

On April 6, 1789, following the ratification of the Constitution, George Washington was selected president; he accepted the position on April 14, 1789, and his inauguration was scheduled in New York City (the nation's capitol) for April 30, 1789. A leading New York Daily newspaper reported on the planned inaugural:

[O]n the morning of the day on which our illustrious President will be invested with his office, the bells will ring at nine o'clock, when the people may go up to the house of God and in a solemn manner commit the new government, with its important train of consequences, to the holy protection and blessing of the most high. An early hour is prudently fixed for this peculiar act of devotion and . . . is designed wholly for prayer. (New York Daily Advertiser, Thursday, April 23, 1789, p. 2)

The details of this report are in line with Congressional resolutions. On April 27, three days before the inauguration, the Senate:

Resolved, That after the oath shall have been administered to the President, he, attended by the Vice President and members of the Senate and House of Representatives, shall proceed to St. Paul's Chapel, to hear divine service. (Annals of Congress, Vol 1, p. 25, April 27, 1789; available online at Library of Congress.)

After being sworn in, George Washington delivered his "Inaugural Address" to a joint session of Congress. In it Washington declared:

[I]t would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a Government instituted by themselves . . . . In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow-citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency; and . . . can not be compared with the means by which most governments have been established without some return of pious gratitude, along with an humble anticipation of the future blessings which the past seem to presage.

[W]e ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained . . . .

Messages and Papers of the Presidents, George Washington, Richardson, ed., vol. 1, p.44-45

Following his address, the Annals of Congress reported that:

The President, the Vice-President, the Senate, and House of Representatives, &c., then proceeded to St. Paul's Chapel, where Divine service was performed by the chaplain of Congress.

These people obviously didn't get the memo about the Constitution creating a secular government.

Those who continue to claim that "the Constitution is a secular document" didn't get the memo from George Washington and the Founding Fathers. There is simply no evidence that anyone who participated in the creation and ratification of the U.S. Constitution believed it to be "a secular document," that is, one that required a "separation" of God and government.

But that doesn't stop Secular Humanists from promoting their religion of secularism by claiming that "the Constitution is a secular document."

One such article on the internet, passed on by many Secular Humanists, is "Little-Known U.S. Document Proclaims America's Government is Secular" from The Early America Review, Summer 1997, by Jim Walker. The article is reproduced in the left-hand column below, and a response is found in the right-hand column.

Little-Known U.S. Document Signed by President Adams Proclaims America's Government Is Secular |

|

|

A few Christian fundamentalists attempt to convince us to return to the Christianity of early America, yet according to the historian, Robert T. Handy, "No more than 10 percent-- probably less-- of Americans in 1800 were members of congregations." |

It's possible that in 1800 only about 10% of Americans could vote. Women could not vote. People who did not own property could not vote in many jurisdictions. R.J. Rushdoony notes:

In colonial New England the covenantal concept of church and state was applied. Everyone went to church, but only a limited number had voting rights in the church and therefore the state, because there was a coincidence of church membership and citizenship. The others were no less believers, but the belief was that only the responsible must be given responsibility. One faith, one law, and one standard of justice did not mean democracy. The heresy of democracy has since then worked havoc in church and state, and it has worked towards reducing society to anarchy. Is historian Robert Handy claiming that in 1800 ninety percent of Americans claimed to be secular humanists? That would be insane to claim. Truly insane. Perhaps it's Jim Walker who's insane. |

|

The Founding Fathers, also, rarely practiced Christian orthodoxy.

|

Another truly ludicrous claim. The vast majority of Founding Fathers always practiced Christian orthodoxy. Walker has in mind a half dozen men among the Founders who were not orthodox in their own personal beliefs, even though they may also have regularly attended orthodox Christian churches, or as civil magistrates made Trinitarian declarations and enforced Biblical laws. David Barton, in his book Orignial Intent , provides biographical sketches of over 200 people who could be considered

"Founding Fathers," and more could be listed, such as those who were delegated by the colonies to participate in the state ratifying conventions. Probably 99% of these men were orthodox Christians and opposed the idea of the federal government denying its duty to obey God and declaring itself "secular" with the power to impose secularism on the states. , provides biographical sketches of over 200 people who could be considered

"Founding Fathers," and more could be listed, such as those who were delegated by the colonies to participate in the state ratifying conventions. Probably 99% of these men were orthodox Christians and opposed the idea of the federal government denying its duty to obey God and declaring itself "secular" with the power to impose secularism on the states. |

| Although they supported the free exercise of any religion, they understood the dangers of religion. | It would be interesting to see if Walker could actually name a single Founding Father who understood -- much less publicly spoke, or codified into law -- anything about "the dangers of religion." Probably every single one of them publicly proclaimed the value and positive benefits of religion. An example of this is the Northwest Ordinance of 1789, legally put into force by the same Founding Congress that approved the First Amendment. The NW Ordinance served as a blueprint for territories seeking admission to the Union, many of whose constitutions echoed the statement in Article III of the NWO, that religion is "necessary for good government and the happiness of mankind."

"Dangers of religion?" What a preposterous claim. |

| Most of them believed in deism and attended Freemasonry lodges. | Not a single person who signed the Constitution was an atheist or even a deist. Not one. |

| According to John J. Robinson, "Freemasonry had been a powerful force for religious freedom." Freemasons took seriously the principle that men should worship according to their own conscience. Masonry welcomed anyone from any religion or non-religion, as long as they believed in a Supreme Being. Washington, Franklin, Hancock, Hamilton, Lafayette, and many others accepted Freemasonry. | Freemasons were not secularists.

Freedom of conscience was promoted by Christians, not secularists. Christians like Rhode Island's Roger Williams were Theocrats who believed that Baptists should not be compelled to support Presbyterian churches or worship in a way that they believed was not Biblical, but even witchcraft was a crime in Rhode Island. Can Walker name one Freemason who had a hand in creating or ratifying the Constitution who believed that the U.S. should have an atheistic government, empowered to impose secularism on the states and local governments? |

|

The Constitution reflects our founders views of a secular government, protecting the freedom of any belief or unbelief. |

These secular views did not exist.

Sure, an atheist could believe God did not exist, but he could not hold political office in any government in the New World. The Constitution did not change that. Only the secularized Supreme Court did that -- and not until 1961. The Constitution itself (especially the First Amendment) protected the rights of the states to discriminate against unbelievers. |

| The historian, Robert Middlekauff, observed, "the idea that the Constitution expressed a moral view seems absurd. There were no genuine evangelicals in the Convention, and there were no heated declarations of Christian piety." | Clinton Rossiter, a better-known constitutional historian, might disagree. Even if there were no "genuine evangelicals in the Convention" (they all lied about being Christians?) there were no genuine secularists either. And as for declarations of Christian piety, Middlekauff should have been there. |

George Washington |

|

|

Much of the myth of Washington's alleged Christianity came from Mason Weems influential book, "Life of Washington." The story of the cherry tree comes from this book and it has no historical basis. Weems, a Christian minister portrayed Washington as a devout Christian, yet Washington's own diaries show that he rarely attended Church. |

I am not a member of any church, and I am a stark-raving mad fundamentalist theocrat. Washington's diaries do not say "I rarely attend church." In fact, he regularly attended church, but silently protested certain sacramental features of church. As Commander in Chief of the Continental Armies, he ordered regular church attendance by the troops, and urged them to become better Christians. |

|

Washington revealed almost nothing to indicate his spiritual frame of mind, hardly a mark of a devout Christian. |

What is it that qualifies Walker to be judge of what constitutes a devout Christian? US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall said of Washington,

|

| In his thousands of letters, the name of Jesus Christ never appears. He rarely spoke about his religion, but his Freemasonry experience points to a belief in deism. Washington's initiation occurred at the Fredericksburg Lodge on 4 November 1752, later becoming a Master mason in 1799, and remained a freemason until he died. | In The Writings of George Washington, JC Fitzpatrick, ed., Wash. DC: US Gov't Printing Office, 1932, Vol 15, p.55 we read Washington telling the Delaware Indian Chiefs,

On June 3, 1783, Washington sent a circular letter to the governors of the thirteen states from his headquarters in Newburgh, New York. He closed that letter with a prayer that God would

So the name "Jesus Christ" may not have appeared, but Who else is Washington referring to when he speaks of "the Divine Author of our blessed religion?" (And shouldn't Washington at least have said, "the Divine Author of our dangerous religion?" See also Jefferson's remarks below.) |

|

To the United Baptist Churches in Virginia in May, 1789, Washington said that every man "ought to be protected in worshipping the Deity according to the dictates of his own conscience." |

This obviously proves that Washington was an atheist. Would Jerry Falwell have disagreed with freedom to worship according to conscience? |

|

After Washington's death, Dr. Abercrombie, a friend of his, replied to a Dr. Wilson, who had interrogated him about Washington's religion replied, "Sir, Washington was a Deist." |

Was Abercrombie offended that Washington disagreed with Abercrombie's theories of certain sacraments? Unfortunately, clerics often call their theological brethren "heretic" and other labels over relatively insignificant differences of theological opinion. |

Thomas Jefferson |

|

|

Even most Christians do not consider Jefferson a Christian. |

Even if Jefferson was not a Christian, this does not prove that he supported the idea of a "secular constitution," one which gave the federal government power to prohibit freedom of religion among the states (which is precisely what the myth of "separation of church and state" does). |

| In many of his letters, he denounced the superstitions of Christianity. | What are "the superstitions" of Christianity. Can one deny these parts of man-made Christianity and still be a genuine Christian? What qualifies Walker to determine this? Jefferson himself claimed to be a Christian. |

| He did not believe in spiritual souls, angels or godly miracles. Although Jefferson did admire the morality of Jesus, Jefferson did not think him divine, nor did he believe in the Trinity or the miracles of Jesus. In a letter to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787, he wrote, "Question with boldness even the existence of a god." | None of this proves that Jefferson believed the Constitution conferred upon the federal government the power to secularize the states. |

|

Jefferson believed in materialism, reason, and science. |

Oooohhh, he believed in reason. Obviously that proves Jefferson believed that the Constitution was a secular document, because Christians don't believe in reason. |

| He never admitted to any religion but his own. In a letter to Ezra Stiles Ely, 25 June 1819, he wrote, "You say you are a Calvinist. I am not. I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know." | Calvinism was a "sect" of Christianity. Jefferson was not of that sect, but he claimed to be a generic Christian.

Sharing a hope nurtured by many Americans in the early nineteenth century, Jefferson anticipated a re-establishment of the Christian religion in its "original purity" in the United States.

|

| Now, consider the logic of Walker's line of argument. All his premises are false. Jefferson did claim a religion for himself, and it wasn't the religion of Secular Humanism. But even if all of Walker's claims about Jefferson's personal beliefs are true, how do these premises logically lead to the conclusion that the Constitution was a secular document, when Jefferson was in France at the time the Constitution was drafted, signed, and ratified? How do Jefferson's personal subjective beliefs determine the legal, objective character of a charter he did not participate in creating? | |

John Adams |

|

John Adams John Adams |

|

|

Adams, a Unitarian, flatly denied the doctrine of eternal damnation. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson, he wrote: |

Universalists -- those who believe everyone gets saved in the end -- still consider themselves Christians, and are not necessarily secularists |

|

"I almost shudder at the thought of alluding to the most fatal example of the abuses of grief which the history of mankind has preserved -- the Cross. Consider what calamities that engine of grief has produced!" |

Walker has totally ripped this passage out of context. It proves nothing about Adams' antipathy to Christianity. The next sentence reads:

I agree with Adams about "knavish priests." Adams is talking about how hypocrites exploit the death of good people. Go here and read the next two pages. It will take 2 minutes. Obviously Walker didn't feel it necessary to invest that amount of time in creating a public attack on Christianity. Anyone who quotes John Adams in this way in support of the proposition that the Constitution is legally and objectively secularist should be ashamed of himself. |

|

In his letter to Samuel Miller, 8 July 1820, Adams admitted his unbelief of Protestant Calvinism: "I must acknowledge that I cannot class myself under that denomination." |

There are millions of Christian who do not consider themselves Calvinists who nevertheless consider themselves Christians. Walker obviously does not understand this elementary distinction, and thus disqualifies himself from being our guide to the spiritual foundation of our nation. |

|

In his, "A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America" [1787-1788], John Adams wrote: |

This is a defense of the state constitutions, not, "as some have imagined," the U.S. federal constitution. It was written from 4 Oct 1786 to 26 Dec 1787. The state constitutions at this time were all Christian Theocratic constitutions. |

|

"The United States of America have exhibited, perhaps, the first example of governments erected on the simple principles of nature; and if men are now sufficiently enlightened to disabuse themselves of artifice, imposture, hypocrisy, and superstition, they will consider this event as an era in their history. Although the detail of the formation of the American governments is at present little known or regarded either in Europe or in America, it may hereafter become an object of curiosity. It will never be pretended that any persons employed in that service had interviews with the gods, or were in any degree under the influence of Heaven, more than those at work upon ships or houses, or laboring in merchandise or agriculture; it will forever be acknowledged that these governments were contrived merely by the use of reason and the senses. |

In context, this is comparing the state constitutions (which were all Theocratic, an objection of the French commentator Turgot, against whom Adams is writing) with ancient Greece and Rome. Adams is saying that Christians use reason to determine the structure of governments (e.g., two houses of Congress or a unicameral legislature, etc.) and that "the miseries of Greece" have been avoided without getting a government blueprint handed down from Olympus.

Again, Walker has violently wrenched a passage out of context. |

|

". . . Thirteen governments [of the original states] thus founded on the natural authority of the people alone, without a pretence of miracle or mystery, and which are destined to spread over the northern part of that whole quarter of the globe, are a great point gained in favor of the rights of mankind." |

|

James Madison |

|

|

Called the father of the Constitution, Madison had no conventional sense of Christianity. In 1785, Madison wrote in his Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments: |

Notice that Madison's criticisms of hypocritical, statist clergy are recklessly used to draw a conclusion about Madison's opinions of true Christianity, and further used to prove (somehow) that the Constitution imposes secularism on the Christian states. In his "Memorial and Remonstrance," Madison said legislators should vote against any legislative bill if |

|

"During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity; in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution." |

the policy of the bill is adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity. The first wish of those who enjoy this precious gift, ought to be that it may be imparted to the whole race of mankind. Compare the number of those who have as yet received it with the number still remaining under the dominion of false Religions; and how small is the former! Does the policy of the Bill tend to lessen the disproportion? No; it at once discourages those who are strangers to the light of (revelation) from coming into the Region of it; and countenances, by example the nations who continue in darkness, in shutting out those who might convey it to them. Instead of levelling as far as possible, every obstacle to the victorious progress of truth, the Bill with an ignoble and unchristian timidity would circumscribe it, with a wall of defence, against the encroachments of error. |

|

"What influence, in fact, have ecclesiastical establishments had on society? In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of the civil authority; on many instances they have been seen upholding the thrones of political tyranny; in no instance have they been the guardians of the liberties of the people. Rulers who wish to subvert the public liberty may have found an established clergy convenient auxiliaries. A just government, instituted to secure and perpetuate it, needs them not." |

An "ecclesiastical establishment" means Baptists are taxed to support Presbyterian clergy. This is a completely different issue than whether cannibalism should be a crime. A Christian Theocracy can avoid taxing Baptists without extending religious freedom to cannibals.

As President, Madison did not behave as though he were obligated to impose secularism or blackout Christainity. |

Benjamin Franklin |

|

|

Although Franklin received religious training, his nature forced him to rebel against the irrational tenets of his parents Christianity. His Autobiography revels his skepticism, "My parents had given me betimes religions impressions, and I received from my infancy a pious education in the principles of Calvinism. But scarcely was I arrived at fifteen years of age, when, after having doubted in turn of different tenets, according as I found them combated in the different books that I read, I began to doubt of Revelation itself. |

Franklin's adolescent rebellion was recanted later in life. (Though that doesn't mean Franklin became a Calvinist.) |

|

". . . Some books against Deism fell into my hands. . . It happened that they wrought an effect on my quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a through Deist." |

All of this took place decades before the Constitution was drafted. During the Convention, Franklin urged public prayer; hardly the work of a secularist.

Even if Franklin was a "deist" (he was not -- he believed in a form of Providence), that does not prove he was a secularist. He was not. |

|

In an essay on "Toleration," Franklin wrote: |

|

|

"If we look back into history for the character of the present sects in Christianity, we shall find few that have not in their turns been persecutors, and complainers of persecution. The primitive Christians thought persecution extremely wrong in the Pagans, but practiced it on one another. The first Protestants of the Church of England blamed persecution in the Romish church, but practiced it upon the Puritans. These found it wrong in the Bishops, but fell into the same practice themselves both here [England] and in New England." |

None of this proves that Franklin believed in the separation of God and government. He did not.

Franklin proposed a Day of Fasting in Pennsylvania, which a true separationist would never do. He proclaimed: and he prayed that The public nature of Franklin's prayer runs counter to the ACLU's version of "separation of church and state," and no Deist believes that God "interposes" and "confounds" and "defeats" any human undertaking. This is not the act of a Deist (as the word is popularly understood). In 1749, he wrote:

Jerry Falwell is panting for a "deistic" theocracy like Franklin's. |

|

Dr. Priestley, an intimate friend of Franklin, wrote of him: |

|

|

"It is much to be lamented that a man of Franklin's general good character and great influence should have been an unbeliever in Christianity, and also have done as much as he did to make others unbelievers" (Priestley's Autobiography) |

|

Thomas Paine |

|

|

This freethinker and author of several books, influenced more early Americans than any other writer. Although he held Deist beliefs, he wrote in his famous The Age of Reason: |

But the Age of Reason was universally rejected by the Founders, including Adams and Franklin. Get the story here. |

|

"I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my church. " |

|

|

"Of all the systems of religion that ever were invented, there is no more derogatory to the Almighty, more unedifiying to man, more repugnant to reason, and more contradictory to itself than this thing called Christianity. " |

|

The U.S. Constitution |

|

|

The most convincing evidence that our government did not ground itself upon Christianity comes from the very document that defines it-- the United States Constitution. |

|

|

If indeed our Framers had aimed to found a Christian republic, it would seem highly unlikely that they would have forgotten to leave out their Christian intentions in the Supreme law of the land. In fact, nowhere in the Constitution do we have a single mention of Christianity, God, Jesus, or any Supreme Being. There occurs only two references to religion and they both use exclusionary wording. The 1st Amendment's says, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion. . ." and in Article VI, Section 3, ". . . no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States." |

It was Christians -- and ecclesiastics in particular -- that opposed giving the federal government any authority in the area of religion. If the Baptists had suggested the wording for a mention of Jesus, the Presbyterians would have opposed it. There were no atheists in the Constitutional Convention arguing in favor of a secular (secularizing) government.

A "religious test" meant one that excluded Baptists or required Episcopalians. Every single state in the union had a generic religious test (belief in God) and these tests were not "discovered" to be "unconstitutional" until 1961. More details. |

|

Thomas Jefferson interpreted the 1st Amendment in his famous letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in January 1, 1802: |

|

|

"I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between church and State." |

|

|

Some Religious activists try to extricate the concept of separation between church and State by claiming that those words do not occur in the Constitution. Indeed they do not, but neither does it exactly say "freedom of religion," yet the First Amendment implies both. |

|

|

As Thomas Jefferson wrote in his Autobiography, in reference to the Virginia Act for Religious Freedom: |

|

|

"Where the preamble declares, that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed by inserting "Jesus Christ," so that it would read "A departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion;" the insertion was rejected by the great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mohammedan, the Hindoo and Infidel of every denomination." |

Walker is taking this out of context. Nobody is disputing that the Hindoo is protected by the First Amendment. Nobody. But what Walker is trying to say is that the "author of our Holy Religion" is not Jesus Christ. Walker is just plain silly. In 1812 Madison issued an official proclamation that the nation would pray to "the Sovereign of the Universe and the Benefactor of Mankind" "that He would inspire all nations with a love of justice and of concord and with a reverence for the unerring precept of our holy religion to do to others as they would require that others should do to them." Now what "holy religion" was Madison speaking about? Hinduism? Secularism? Walker doesn't know what he's talking about, nor what Jefferson was talking about. See also Washington's statement above. |

|

James Madison, perhaps the greatest supporter for separation of church and State, and whom many refer to as the father of the Constitution, also held similar views which he expressed in his letter to Edward Livingston, 10 July 1822: |

|

|

"And I have no doubt that every new example will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that religion & Govt will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together." |

"Religion" here means specific denominations of Christianity. It is beyond dispute that Madison and all the other Founding Fathers believed that God was sovereign over government, and that government had a duty to acknowledge God, not to be secular. |

|

Today, if ever our government needed proof that the separation of church and State works to ensure the freedom of religion, one only need to look at the plethora of Churches, temples, and shrines that exist in the cities and towns throughout the United States. Only a secular government, divorced from religion could possibly allow such tolerant diversity. |

Not a single one of the Founding Fathers believed that government should be divorced from generic Christianity. |

The Declaration of Independence |

|

|

Many Christians who think of America as founded upon Christianity usually present the Declaration as "proof." The reason appears obvious: the document mentions God. However, the God in the Declaration does not describe Christianity's God. It describes "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God." This nature's view of God agrees with deist philosophy but any attempt to use the Declaration as a support for Christianity will fail for this reason alone. |

None of the delegates to Philadelphia, nor the states who sent them, would agree with Walker's claim. A deist God does not supernaturally intervene in human history in response to prayer ("Providence"), as the God of the Declaration of Independence does. The Declaration is not deist. It champions a belief in "Providence," the opposite of deism.

The "laws of Nature's God" is a way of talking about the Bible. |

|

More significantly, the Declaration does not represent the law of the land as it came before the Constitution. The Declaration aimed at announcing their separation from Great Britain and listed the various grievances with the "thirteen united States of America." The grievances against Great Britain no longer hold, and we have more than thirteen states. Today, the Declaration represents an important historical document about rebellious intentions against Great Britain at a time before the formation of our independent government. Although the Declaration may have influential power, it may inspire the lofty thoughts of poets, and judges may mention it in their summations, it holds no legal power today. Our presidents, judges and policemen must take an oath to uphold the Constitution, but never to the Declaration of Independence. |

Whoever "Jim Walker is," he doesn't understand "the law of the land." David Barton writes:

This argument is of recent origin, however, for well into the twentieth century, the Declaration and the Constitution were viewed as interdependent rather than as independent documents. In fact, the U. S. Supreme Court declared: [T]he latter [the Constitution] is but the body and the letter of which the former [the Declaration of Independence] is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. [52] No other conclusion logically can be reached since the Constitution directly attaches itself to the Declaration in Article VII by declaring: Done in convention by the unanimous consent of the States present the seventeenth day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty seven, and of the independence of the United States of America the twelfth. (emphasis added) Additional evidence that the framers viewed the Declaration as inseparable from the Constitution is seen by the fact that Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, et al., dated their government acts under the Constitution from the Declaration rather than the Constitution. [53] Furthermore, the admission of territories as States into the Union was often predicated on an assurance by the State that the State’s. . . . . . constitution, when formed, shall be republican, and not repugnant to the Constitution of the United States and the principles of the Declaration of Independence. [54] The framers believed that the Declaration provided the core values by which the Constitution was to operate, and that the Constitution was not to be interpreted apart from those values. As John Quincy Adams explained in his famous oration, The Jubilee of the Constitution: [T]he virtue which had been infused into the Constitution of the United States . . . was no other than the concretion of those abstract principles which had been first proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. . . . This was the platform upon which the Constitution of the United States had been erected. Its virtues, its republican character, consisted in its conformity to the principles proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and as its administration . . . was to depend upon the . . . virtue, or in other words, of those principles proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and embodied in the Constitution of the United States. [55] The framers never imagined that the Constitution could be interpreted to violate the values they had erected in the Declaration; for, under America’s government as originally established, a violation of the principles of the Declaration was just as serious as a violation of the provisions of the Constitution. Nonetheless, courts over the past half-century have isolated the two documents, now making them mutually exclusive. [52] Ry. Co. v. Ellis, 165 U. S. 150, 160 (1897). [53] See proclamations by George Washington on August 14, 1790; John Adams on July 22, 1797; Thomas Jefferson on July 16, 1803; James Madison on August 9, 1809; James Monroe on April 28, 1818; John Quincy Adams on March 17, 1827 Andrew Jackson on May 11, 1829, etc. 1-2 James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents 1789-1897 (1899). [54] 8 The Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America 31-48 (George P. Sanger, ed., 1866) (thirty-eighth Congress, Session 1, Chapter 37, Section 4, Colorado’s enabling act of March 21, 1864; Chapter 36, Section 4, Nevada’s enabling act of March 21, 1864; Chapter 59, Section 4, Nebraska’s enabling act of April 19, 1864). 34 The Statutes at Large of the United States of America (1907), (fifty-ninth Congress, Session 1, Chapter 3335, Section 3, Oklahoma’s enabling act of June 16, 1906; etc.). [55] John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution. A Discourse Delivered at the Request of the New York Historical Society, in the City of New York, on Tuesday, the 30th of April 1789, at 83 (1839). The U.S. Supreme Court has said that the oath to "support the Constitution" includes support for the entire "organic law" of the U.S., which includes the Declaration of Independence. |

|

Of course the Declaration depicts a great political document, as it aimed at a future government upheld by citizens instead of a religious monarchy. It observed that all men "are created equal" meaning that we all come inborn with the abilities of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That "to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men." The Declaration says nothing about our rights secured by Christianity, nor does it imply anything about a Christian foundation. |

Another fallacy: the false antithesis: either you believe in a "secular constitution" or you believe in "a religious monarchy."

The Declaration says our rights come from God. How can Walker miss this obvious point? (Maybe he doesn't. Maybe he just hopes his readers will.) Read about "The Laws of Nature and of Nature's God." There is plenty that "implies" a Christian foundation. No other inference is sane. A Buddhist foundation? An atheist foundation? |

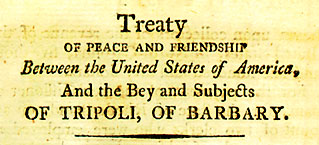

Treaty of Tripoli |

|

|

|

|

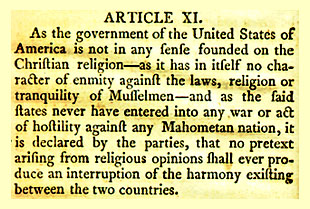

Unlike governments of the past, the American Fathers set up a government divorced from religion. The establishment of a secular government did not require a reflection to themselves about its origin; they knew this as an unspoken given. However, as the U.S. delved into international affairs, few foreign nations knew about the intentions of America. For this reason, an insight from at a little known but legal document written in the late 1700s explicitly reveals the secular nature of the United States to a foreign nation. Officially called the "Treaty of peace and friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli, of Barbary," most refer to it as simply the Treaty of Tripoli. In Article 11, it states: |

In 1783 the US and Britain ended the Revolutionary war with the Paris Peace Treaty. The treaty was written by John Adams, John Jay, and Ben Franklin, and the winners (The United States) forced the losers (Great Britain) to sign it. Its very first words are:

http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/paris.htm Clearly America WAS a Christian nation, so any claim that it "never" was is inaccurate. Nothing legally changed America from a Christian nation to a non-Christian one. Certainly the Treaty with Tripoli did not. |

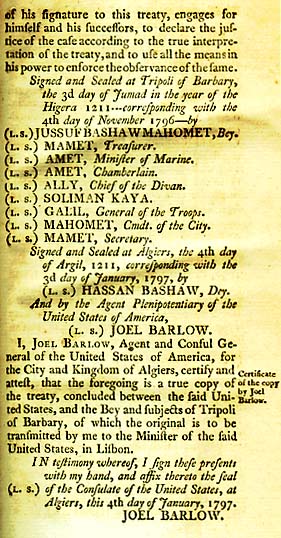

Joel Barlow, U.S. Consul General of Algiers Joel Barlow, U.S. Consul General of AlgiersCopyright National Portait Gallery Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource NY |

Barlow was an apostate chaplain. Though at one time a professing Christian, he grew to hate Christianity.

Imagine that a mentally disturbed Clerk at the U.S. Supreme Court switched Court opinions, replacing the real decision of the Court with a "decision" purporting to rule that Jews were not human beings and should be interred in concentration camps and gassed. It takes a few weeks before anyone notices, but eventually the Court "reverses" the bogus decision. Would anyone seriously maintain that the "real" position of the U.S. government is anti-semitism and gassing Jews, based on the bogus "decision?" |

|

"As the Government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquillity, of Musselmen; and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries." |

This line about "not in any sense founded on the Christian religion" is manifestly false. America is -- in some sense at least -- founded on the Christian religion. The purpose of the treaty was to assure the Muslims that the U.S. would not attack them solely because they were Muslim. But that wholly-false claim is not necessary to achieve that purpose. It is unclear how that line got in some copies of the treaty, but it was removed the very next time Congress authorized it. |

Article XI from the Treaty of Tripoli Article XI from the Treaty of Tripoli |

|

|

The preliminary treaty began with a signing on 4 November, 1796 (the end of George Washington's last term as president). Joel Barlow, the American diplomat served as counsel to Algiers and held responsibility for the treaty negotiations. Barlow had once served under Washington as a chaplain in the revolutionary army. He became good friends with Paine, Jefferson, and read Enlightenment literature. Later he abandoned Christian orthodoxy for rationalism and became an advocate of secular government. Barlow, along with his associate, Captain Richard O'Brien, et al, translated and modified the Arabic version of the treaty into English. From this came the added Amendment 11. Barlow forwarded the treaty to U.S. legislators for approval in 1797. Timothy Pickering, the secretary of state, endorsed it and John Adams concurred (now during his presidency), sending the document on to the Senate. The Senate approved the treaty on June 7, 1797, and officially ratified by the Senate with John Adams signature on 10 June, 1797. All during this multi-review process, the wording of Article 11 never raised the slightest concern. The treaty even became public through its publication in The Philadelphia Gazette on 17 June 1797. |

Charles I. Bevans is the editor of the U.S. treaties collection published by the State Department (Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949 [Department of State, 1974]). See the translation of Article 12. It differs markedly from Barlow's.

On Article 11, Bevans has the following:

|

|

So here we have a clear admission by the United States that our government did not found itself upon Christianity. Unlike the Declaration of Independence, this treaty represented U.S. law as all treaties do according to the Constitution (see Article VI, Sect. 2). |

There is nothing clear about this phrase. Read that link to get the whole story. Walker doesn't have it. |

|

Although the Christian exclusionary wording in the Treaty of Tripoli only lasted for eight years and no longer has legal status, it clearly represented the feelings of our Founding Fathers at the beginning of the U.S. government. |

The only thing that is clear about this really weird phrase is that it was removed the very next time the treaty was renegotiated. This is a desperate grasping at straws in an effort to avoid the overwhelming evidence that America is a Christian nation. |

Signers of the Treaty of Tripoli Signers of the Treaty of Tripoli |

|

Common Law |

|

|

According to the Constitution's 7th Amendment: "In suits at common law. . . the right of trial by jury shall be preserved; and no fact, tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States than according to the rules of the common law." |

|

|

Here, many Christians believe that common law came from Christian foundations and therefore the Constitution derives from it. They use various quotes from Supreme Court Justices proclaiming that Christianity came as part of the laws of England, and therefore from its common law heritage. |

|

|

But one of our principle Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson, elaborated about the history of common law in his letter to Thomas Cooper on February 10, 1814: |

Jefferson was wrong. Everybody disagreed with him. Jefferson was not mainstream on all issues. Especially this one. |

|

"For we know that the common law is that system of law which was introduced by the Saxons on their settlement in England, and altered from time to time by proper legislative authority from that time to the date of Magna Charta, which terminates the period of the common law. . . This settlement took place about the middle of the fifth century. But Christianity was not introduced till the seventh century; the conversion of the first christian king of the Heptarchy having taken place about the year 598, and that of the last about 686. Here then, was a space of two hundred years, during which the common law was in existence, and Christianity no part of it. |

The Common Law and Christianity |

|

". . . if any one chooses to build a doctrine on any law of that period, supposed to have been lost, it is incumbent on him to prove it to have existed, and what were its contents. These were so far alterations of the common law, and became themselves a part of it. But none of these adopt Christianity as a part of the common law. If, therefore, from the settlement of the Saxons to the introduction of Christianity among them, that system of religion could not be a part of the common law, because they were not yet Christians, and if, having their laws from that period to the close of the common law, we are all able to find among them no such act of adoption, we may safely affirm (though contradicted by all the judges and writers on earth) that Christianity neither is, nor ever was a part of the common law." |

|

|

In the same letter, Jefferson examined how the error spread about Christianity and common law. Jefferson realized that a misinterpretation had occurred with a Latin term by Prisot, "*ancien scripture*," in reference to common law history. The term meant "ancient scripture" but people had incorrectly interpreted it to mean "Holy Scripture," thus spreading the myth that common law came from the Bible. Jefferson writes: |

|

|

"And Blackstone repeats, in the words of Sir Matthew Hale, that 'Christianity is part of the laws of England,' citing Ventris and Strange ubi surpa. 4. Blackst. 59. Lord Mansfield qualifies it a little by saying that 'The essential principles of revealed religion are part of the common law." In the case of the Chamberlain of London v. Evans, 1767. But he cites no authority, and leaves us at our peril to find out what, in the opinion of the judge, and according to the measure of his foot or his faith, are those essential principles of revealed religion obligatory on us as a part of the common law." |

|

|

Thus we find this string of authorities, when examined to the beginning, all hanging on the same hook, a perverted expression of Priscot's, or on one another, or nobody." |

|

|

The Encyclopedia Britannica, also describes the Saxon origin and adds: "The nature of the new common law was at first much influenced by the principles of Roman law, but later it developed more and more along independent lines." Also prominent among the characteristics that derived out of common law include the institution of the jury, and the right to speedy trial. |

Jefferson was wrong. Read the link: |

Christian Sources |

|

|

Virtually all the evidence that attempts to connect a foundation of Christianity upon the government rests mainly on quotes and opinions from a few of the colonial statesmen who had professed a belief in Christianity. Sometimes the quotes come from their youth before their introduction to Enlightenment ideas or simply from personal beliefs. But statements of beliefs, by themselves, say nothing about Christianity as the source of the U.S. government. |

Not "a few" -- the vast majority.

This last statement is correct. The U.S. Supreme Court declared that America is a Christian nation, not a secular one. This is the legal effect of the laws and charters of the U.S. government. |

|

There did occur, however, some who wished a connection between church and State. Patrick Henry, for example, proposed a tax to help sustain "some form of Christian worship" for the state of Virginia. But Jefferson and other statesmen did not agree. In 1779, Jefferson introduced a bill for the Statute for Religious Freedom which became Virginia law. Jefferson designed this law to completely separate religion from government. None of Henry's Christian views ever got introduced into Virginia's or U.S. Government law. |

The Virginia Bill of Rights, Art 16, says:

|

|

Unfortunately, later developments in our government have clouded early history. The original Pledge of Allegiance, authored by Francis Bellamy in 1892 did not contain the words "under God." Not until June 1954 did those words appear in the Allegiance. The United States currency never had "In God We Trust" printed on money until after the Civil War. Many Christians who visit historical monuments and see the word "God" inscribed in stone, automatically impart their own personal God of Christianity, without understanding the Framers Deist context. |

"In God We Trust" goes back to the first steps of Christians onto the North American continent. Same with the phrase "under God."

There is no "deist context." |

|

In the Supreme Court's 1892 Holy Trinity Church vs. United States, Justice David Brewer wrote that "this is a Christian nation." Many Christians use this as evidence. However, Brewer wrote this in dicta, as a personal opinion only and does not serve as a legal pronouncement. Later Brewer felt obliged to explain himself: "But in what sense can [the United States] be called a Christian nation? Not in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or the people are compelled in any manner to support it. On the contrary, the Constitution specifically provides that 'Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.' Neither is it Christian in the sense that all its citizens are either in fact or in name Christians. On the contrary, all religions have free scope within its borders. Numbers of our people profess other religions, and many reject all." |

This is all balderdash. Learn the truth.

Holy Trinity Church v. United States (1892) - Separationist Arguments Answered These quotes are ripped out of context. Justice Brewer said the Trinity decision is not personal opinion, but legal, official, organic truth about the nation. The Trinity decision was self-consciously designed to refute all the ideas promulgated in this article by Walker. |

Conclusion |

A repetitive summary of myths refuted above. |

|

The Framers derived an independent government out of Enlightenment thinking against the grievances caused by Great Britain. Our Founders paid little heed to political beliefs about Christianity. The 1st Amendment stands as the bulkhead against an establishment of religion and at the same time insures the free expression of any belief. The Treaty of Tripoli, an instrument of the Constitution, clearly stated our non-Christian foundation. We inherited common law from Great Britain which derived from pre-Christian Saxons rather than from Biblical scripture. |

|

|

Today we have powerful Christian organizations who work to spread historical myths about early America and attempt to bring a Christian theocracy to the government. If this ever happens, then indeed, we will have ignored the lessons from history. Fortunately, most liberal Christians today agree with the principles of separation of church and State, just as they did in early America. |

|

|

"They all attributed the peaceful dominion of religion in their country mainly to the separation of church and state. I do not hesitate to affirm that during my stay in America I did not meet a single individual, of the clergy or the laity, who was not of the same opinion on this point" |

|

|

-Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835 |

|

Bibliography |

Statement of Rep. Tucker:

At this point, Representative Thomas Tudor Tucker objected to the proposal that Congress ask the President to declare a day of prayer:

Like Patrick Henry and other Christians, Rep. Tucker opposed the new Constitution on the grounds that it did not adequately guard against a European-style monarch and the denial of individual rights. Tucker and Henry, it turns out, were right. Tucker obviously did not believe that the Constitution was a secular document that prohibited the states from declaring days of prayer and thanksgiving. There is absolutely no evidence that Tucker or anyone else present in Congress that day believed the new Constitution imposed atheism on the theistic nation. What was the basis of Tucker's objection to Congress declaring a day of prayer? Tucker was an anti-federalist who believed in the doctrine embodied in the Tenth Amendment: that the federal Constitution is a document of enumerated powers. Congress was given no power in the Constitution to act in the area of religion. Presumably, Tucker would have opposed national Prohibition for the same reason -- not because he wanted Americans to be drunkards. To get an idea of Tucker's beliefs, South Carolina's Constitution had the following requirements: Article III. [State officers and privy council to be] all of the Protestant religion. Article XII. ... no person shall be eligible to a seat in the said senate unless he be of the Protestant religion. Article XII... . The qualifications of electors shall be that every free white man, and no other person, who acknowledges the being of a God, and believes in the future states of rewards and punishments . . . [shall be eligible to vote]. No person shall be eligible to sit in the house of representative unless he be of the Protestant religion. . . . Article XXI. ... no minister of the gospel or public preachers of any religious persuasion, while he continues in the exercise of his pastoral function, and for two years after, shall be eligible either as governor, lieutenant-governor, a member of the senate, house of representatives, or privy council in this State. Article XXXVIII. That all persons and religious societies who acknowledge that there is one God, and a future state of rewards and punishments, and that God is publicly to be worshipped, shall be freely tolerated. The Christian Protestant religion shall be deemed, and is hereby constituted and declared to be, the established religion of this State. . . . the respective societies of the Church of England that are already formed in this State for the purpose of religious worship, shall still continue incorporate and hold the religious property now in their possession. And that whenever fifteen or more male persons, not under twenty-one years of age, professing the Christian Protestant religion, and agreeing to unite themselves in a society for the purposes of religious worship, they shall (on complying with the terms hereinafter mentioned) be ... esteemed and regarded in law as of the established religion of the State, and on a petition to the legislature shall be entitled to be incorporated and to enjoy equal privileges. ... each society so petitioning shall have agreed to and subscribed in a book the following five articles, without which no agreement or union of men upon pretence of religion, shall entitle them to be incorporated and esteemed as a church of the established religion in this State:

No person shall, by law, be obliged to pay towards the maintenance and support of a religious worship that he does not freely join in, or has not voluntarily engaged to support. But the churches, chapels, parsonages, glebes, and all other property now belonging to any societies of the Church of England, or any other religious societies, shall remain and be secured to them forever. Notice that both blacks and clergy were prohibited from being governor. Silly rules that have no basis in "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God." |

|

Borden, Morton, "Jews, Turks, and Infidels," The University of North Carolina Press, 1984 |

|

|

Boston, Robert, "Why the Religious Right is Wrong About Separation of Church & State, "Prometheus Books, 1993 |

|

|

Boston, F. Andrews, et al, "The Writings of George Washington," (12 Vols.), Charleston, S.C., 1833-37 |

|

|

Fitzpatrick, John C., ed., "The Diaries of George Washington, 1748-1799," Houghton Mifflin Company: Published for the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union, 1925 |

|

|

Gay, Kathlyn, "Church and State,"The Millbrook Press," 1992 |

|

|

Handy, Robert, T., "A History of the Churches in U.S. and Canada," New York: Oxford University Press, 1977 |

|

|

Hayes, Judith, "All those Christian Presidents," [The American Rationalist, March/April 1997] |

|

|

Kock, Adrienne, ed., "The American Enlightenment: The Shaping of the American Experiment and a Free Society," New York: George Braziller, 1965 |

|

|

Mapp, Jr, Alf J., "Thomas Jefferson," Madison Books, 1987 |

|

|

Middlekauff, Robert, "The Glorious Cause," Oxford University Press, 1982 |

|

|

Miller, Hunter, ed., "Treaties and other International Acts of the United States of America," Vol. 2, Documents 1-40: 1776-1818, United States Government Printing Office, Washington: 1931 |

|

|

Peterson, Merrill D., "Thomas Jefferson Writings," The Library of America, 1984 |

|

|

Remsburg, John E., "Six Historic Americans," The Truth Seeker Company, New York |

|

|

Robinson, John J., "Born in Blood," M. Evans & Company, New York, 1989 |

|

|

Roche, O.I.A., ed, "The Jefferson Bible: with the Annotated Commentaries on Religion of Thomas Jefferson," Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1964 |

|

|

Seldes, George, ed., "The Great Quotations," Pocket Books, New York, 1967 |

|

|

Sweet, William W., "Revivalism in America, its origin, growth and decline," C. Scribner's Sons, New York, 1944 |

|

|

Woodress, James, "A Yankee's Odyssey, the Life of Joel Barlow," J. P. Lippincott Co., 1958 |

|

|

Encyclopedia sources: |

|

|

Common law: Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. 6, "William Benton, Publisher, 1969 |

|

|

Declaration of Independence: MicroSoft Encarta 1996 Encyclopedia, MicroSoft Corp., Funk & Wagnalls Corporation. |

|

|

In God We Trust: MicroSoft Encarta 1996 Encyclopedia, MicroSoft Corp., Funk & Wagnalls Corporation. |

|

|

Pledge of Allegiance: Academic American Encyclopedia, Vol. 15, Grolier Incorporated, Danbury, Conn., 1988 |

|

|

Special thanks to Ed Buckner, Robert Boston, Selena Brewington and Lion G. Miles, for help in providing me with source materials. |

Another Anti-Secular Interpretation

There is another interpretation of American history which must be acknowledged. It differs from the idea presented on this webpage (that the Constitution perpetuates a Christian nation), though it too refutes the idea that America was intended by her Founders to be a secular nation.

This interpretation holds that a core of America's Founders, such as Madison, Washington, Franklin, and others, rejected Biblical Christianity in favor of another religious view: the religion of occult Humanism. This view holds that the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia was a secret coup d'etat, the true intentions of which were hidden from the Christian majority of America.

- Conspiracy in Philadelphia [pdf] xxxi + 421 + index pages.

What the ACLU advances today -- "Secular Humanism" -- was virtually unknown before Darwin. There was only religious humanism.

Today's popular "Secular Humanism" is also a religion, but it had no influence on America's Founding Fathers. Secular Humanism (through the ACLU and similar secularizing organizations) holds that the Constitution empowers the federal judiciary to remove God and religion from government-run schools and other government institutions.

Not a single person who signed the Constitution believed anything resembling this idea, either in terms of federal power or a secular vision of society. America's non-Calvinist Founders were deeply religious and pious, and believed the government should advance "true religion," and everywhere in Washington D.C. you can see evidence of religion being promoted:

- Riddles in Stone, Secret Architecture of Washington DC - Viddler.com 2:54:44

It will take about 6-8 hours to peruse the links above.

It may well be possible to prove that some of America's leading Founders were opposed to the older Calvinist Theocracy, and preferred a Masonic theocracy. But all of America's Founders advocated some form of Theocracy, and none of them -- not one -- promoted a secular (irreligious) federal leviathan under the religion of statism, which is what we have today, thanks to the secularists. They all believed that the formation of the American Republic was a religious activity, that the primary purpose of public schools was to teach religion, the purpose of government was to promote religion, and that a free government was impossible without religion.

America's Founders would not have applauded anti-religious, anti-Bible organizations like the ACLU and the "Freedom FROM Religion" Foundation. They would have warned them to stop, and denounced them if the proceeded, to attack religion and seek to use the federal government to impose secularism on American society, just as they warned Thomas Paine not to publish Age of Reason and denounced him after he did.